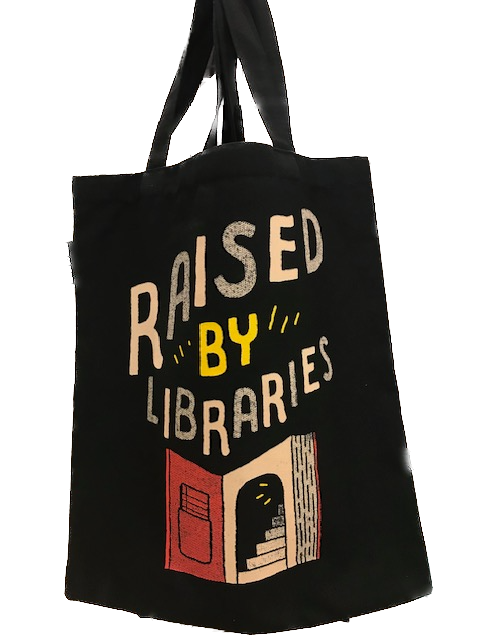

Raised by Libraries but ghosts still linger

175 years later, Libraries are far less radical than one might think, despite opening the gates of intellectual freedom, racism and gatekeeping remains embedded.

My column Raised by Libraries has been sitting in my drafts for months, a recent provocation jolted me out of summer daze chilling on a boat reading my book, compelling me to open up my laptop and finish writing a very real critical reflection on the aftermath of a legislation that led to intellectual freedom.

I never miss the point, in fact I am always on time and bang on the money, I will not be gaslighted by some librarians, in fact their reactions prove the point of mixed feelings after the public library act came to pass, read my observations and weep.

Did you know after 175 years of opening the gates to intellectual freedom that Libraries are still very racist? With the make up of staffing mostly white, middle class, Christian and Jewish, Libraries are not as welcoming and safe as they think they are but the white saviour complex is very much alive.

I was raised by my local community libraries, that so called radical legislation allowed me to at least enter the doors of libraries to borrow books but I was not always welcomed by librarians.

Throughout the 1980s and 90s, I spent every Saturday from 9 to 4, reading, borrowing and ordering books in my local library, that time wasn’t without pain, I was often met with suspicion rather than support. Librarians watching me closely over the rims of their glasses waiting for me to slip up as if expecting me to do something wrong, treating me more like a threat than a young curious reader.

The racial profiling was subtle but constant, disapproving looks, demeaning tone in their voices and comments whilst snorting out of their nose at the books I chose to read left me feeling unwelcome, misunderstood and out of place in a space that should have felt welcoming.

This never stopped me from entering my local library but did make me realise as a child that even librarians are bloody awful people if you are not white, christian, jewish and or middle class.

As a child, reading helped regulate my emotions and more importantly taught me to read when I could not read. Terrible considering my ancestors were the most educated and richest in the world but the treachery that is colonialism destroyed generations of civilisation and it’s history.

As the years passed, I’ve often reflected on the vital role libraries have played in my life, particularly during my educational years and job prospects. Libraries are far more than just places to borrow books, they're community hubs offering access to resources, support and opportunities. Whether you need help navigating a government form, creating an email address, searching for a rare collection item, attending story time with your children, starting a business, looking for a job, recycling electrical items, or even picking up your quarterly waste and recycling bags, the library is there for you. The range of services libraries offer today is truly vast and they continue to adapt to meet the evolving needs of their communities.

Not so long ago, I was surprised to discover a reading room dedicated to Asia and Africa tucked away in an institutional library. Yet it struck me as odd that the walls outside of this reading room prominently celebrate only white, European, Christian, and Jewish librarians, while the contributions of librarians from Commonwealth countries who represent a significant and often overlooked part of British history, remain absent. This erasure reflects a broader pattern of whose stories are valued and remembered.

Had I known about the Asia and Africa reading room back in the early 2000s, researching and writing my dissertation could have broadened my understanding and deepened my research. Library spaces hold not only books but histories and perspectives that challenge the dominant narratives often presented in traditional British institutions that are often hidden away out of sight.

Furthermore community hubs often exist outside the institutional library, despite claims of inclusion and progress many libraries still uphold practices rooted in racism and segregation. The fact that these so called "community hubs" are placed in portable cabins, a mile away from the main library building speaks volumes about who is truly welcome inside a library.

Even with progress libraries continue to face significant challenges, one of the most persistent being the lack of diversity among their staffing, which remains largely white and middle class. At a recent visit to a local community library staff openly shared that one of their biggest struggle is the disconnect, often feeling "lost in translation" when engaging with the diverse populations who walk through their doors. This language and cultural gap remains a major barrier to truly inclusive services. Another pressing concern is that instead of seeing growth in community libraries, we’re witnessing a decline, as many have been shut down due to government cuts.

In addition, there are often derogatory comments questioning why some parents don’t read to their children before bedtime. Economics plays a significant role in this, it’s a reality that many teachers and librarians are reluctant to address. Instead of offering support, librarians wag their fingers at struggling parents, as if parenting isn’t already incredibly hard for those facing financial hardship, exhausted from little sleep and struggling to put food on the table. What’s needed are solutions and empathy, not judgment.

BookTrust estimates that children from low income families are twice as likely to have limited access to books and are less likely to be read to regularly compared to their more affluent peers. This lack of early exposure to reading significantly impacts literacy development and future educational success. Understanding these challenges is essential to closing the literacy gap and supporting families effectively.

I am old enough to remember the racist old white librarian that would sneer down at me for my book choices, remarking “at least you read”.

In the early days of Facebook when Malorie Blackman's Noughts and Crosses made waves not just among young readers but within the library profession itself, among some white librarians there were side-eyes, the passive aggression and criticisms were loud towards racialised young people who connected with her work and towards parents that do not read to their kids before bedtime.

As someone who was raised by libraries, growing up in poverty and a former SEND child, access to libraries and a love of reading helped me defy the odds. I learned to read at a time when I struggled immensely and that journey wasn’t without its challenges. Even now, I carry the weight of those early struggles despite being well spoken, well traveled and well read. Yes, there was a time in my life when I couldn’t read, when I did learn how to it helped compensate for leaving education without notable qualifications, top grades and a Russell Group Education. Falling in love with books and writing, a curiosity to ask questions and research will literally save you.

Fast forward to 2025, 175 years on how radical was the Public Libraries Act, really? The Balfour Declaration is locked away in a vault in a basement at an institutional library that is outspoken about the war in Ukraine but silent on the genocide in Palestine.

Institutional libraries often promote themselves as safe and welcoming spaces but safe for whom? Earlier this year a visibly Muslim woman studying in a Canadian Library was assaulted by an Anti-Muslim Jewish woman who set her hijab on fire.

It is tone deaf to be celebrating so called “surprising” history of radical legislation of public libraries that have supposedly evolved into the welcoming safe spaces without acknowledging contradictions. Sorry to be the bearer of bad news, but when it comes to confronting true systemic injustice, libraries and the institutions behind them aren’t as radical as they claim to be.

I am labelled as “missing the point” when I challenge institutional libraries for adopting a white saviour complex claiming, “We gave you this,” when in reality, so much was stolen through violent oppression of lands that were once home to some of the most educated and advanced societies in the world. British institutional libraries have a responsibility to tell real history of Britain not the softened, comfortable version that flatters the legacy of empire.

I am absolutely NOT missing the point, I am naming a deep ongoing problem about the way colonial institutions like British Libraries and Museums often present themselves as benevolent custodians of knowledge, while sidestepping or sanitising the violent histories through which much of that knowledge and material was acquired.

Framing themselves as saviours in history “we preserved this for you” we opened the gates to intellectual freedom to “dangerous classes” to “your local library was once considered a radical act...” it was met with mixed feelings conveniently ignoring that Brits and Europeans often looted, stole, or coerced their way into possession of items from nations that were systematically oppressed, displaced, and dismantled.

Many of these nations and cultures had thriving, sophisticated systems of knowledge long before colonial interference. In fact colonialism actively worked to erase those systems, burning libraries, dismantling institutions, banning languages, and enforcing Western epistemologies as superior.

I am pointing out a key hypocrisy, institutions that pride themselves on education and historical preservation often fail to educate the public on the full truth of Britain’s colonial past, especially the intellectual and cultural destruction that accompanied physical conquest where millions of collection items now sit in glass boxes of institutional libraries.

I am calling for truth telling, not just symbolic gestures or curated narratives that flatter the empire's legacy in a blog or social media post, British institutional libraries and archives have a duty to tell real British history including the histories of violence, theft and erasure. It's not just a moral responsibility, it’s essential for real learning, reconciliation, and justice.

I’m emotionally intelligent enough to know that when librarians from London to Illinois and Melbourne accuse me of “missing the point,” it often means I’ve hit a nerve. That’s exactly when I know the point has landed.

Yes, it's true that opening the doors of libraries to so called "uncivilised classes" was once seen as a radical act and that the passing of the Public Libraries Act was met with mixed feelings. But framing this as progress without full context risks reinforcing a white saviour narrative. If you're truly committed to education, start by telling truth and stop hiding the truth, intellectual freedom was stolen from many, the British public deserves to know when, how, and why.

Stop glorifying what you deem as a surprising history of this legislation without confronting full historical violence and the lasting consequences public libraries are still grappling with today.

Yes libraries or should I say free access to books nurtured me but they also carry buried stories, silenced voices, and unresolved harm. No matter how much libraries evolve, those ghosts still linger.

Despite its progressive image, the Public Libraries Act was entangled in colonial structures that dictated how knowledge was controlled, who had access to it and which voices were valued.

Cheers to 175 years of “unlocking” intellectual freedom, well done, give yourself a pat on the back. Now go ahead, crack open a beer, have a slice of cake and toast to a version of history that lets you sleep comfortably at night 🙃

Ta ta, Jzk and Free Palestine!

Cx